Mal Lee and Roger Broadie

As evermore schools move to a digital operational base, take responsibility for their on-going evolution and transformation, plan for their unique context, adopt an ever higher order ecology and move ever further along the school evolutionary continuum so the variability between schools will increase. While some schools are in virtual equilibrium at the Paper Based evolutionary stage the pathfinders are moving at pace through the Digital Normalisation stage offering a 24/7/365 mode of schooling fundamentally different and in many respects antithetical to that provided by the traditional school.

Significantly the schools at the Paper Based or even Early Digital evolutionary stages will take years of astute and concerted effort to even reach the Digital Normalisation stage let alone provide a schooling comparable with the pathfinders.

When one recognises that all the other schools globally are at different points along the six stages of the schools’ evolutionary stages continuum you’ll appreciate not only why there will be the increasing school variability but also why governments, education authorities, school decision makers, curriculum designers, teacher educators and educational researchers should begin attuning their thinking and operations to the new reality. .

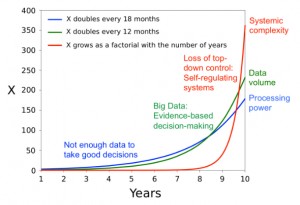

When you add to the significant natural growth that flows when schools shift to a digital operational base, the quest by governments globally to accord ever-greater autonomy and decision making to individual schools and the burgeoning imperative, identified by Helbing (2014) of each operational unit taking prime operational responsibility for its own evolution in an era surging computer power and increasing organisational complexity you’ll appreciate why school variability will be the new norm that all associated with schooling will need to live with.

It is a reality that astute prospective Net Generation parents globally are already aware off, they slowly but most assuredly seeking out those schools they believe will genuinely provide, and vitally will continue to provide, an apposite 21st education.

That said many governments, education authorities and even clusters of schools are still working on the assumption that all schools are basically the same and will continue to be so.

Variability doesn’t appear to have entered most education administrator’s lexicon.

National policies in 2014 are still implemented on the premise that all schools are the same. To assume that schools where but 30% of the teachers use the digital in their teaching should employ the same instructional program as one where the total school community has normalised the 24/7/365 use of the digital and is working within a much higher order, tightly integrated ecology is to show little appreciation of the educational reality of today.

The attributes required of teachers thriving in the latter higher mode of schooling are as indicated (Lee, 2014) significantly different to the former type of school or indeed to be found in the ‘one size fits’ approach found in the national teacher standards and employed by education authority HR units in the hiring and appointing teachers and principals.

Many regional and network staff development programs continue to be mounted on the assumption that all schools in an area are at the same evolutionary point and have the same needs. Pathfinder schools are openly criticised when they declare those common programs are a waste and no longer applicable to their situation.

Technology solutions are still notoriously based on the assumption that all schools must use the standard approach invariably devised by central office techs with seemingly no understanding of the situation in a diverse group of increasingly autonomous schools.

There appears globally in 2014 a pronounced inability by many educational decision makers to understand that every school is unique and that the time honoured ‘one size fits all’ approach has passed its ‘use by date’.

In the same way that many schools have difficulty personalising the student teaching so governments and education authorities seemingly have difficulty in individualising the enhancement of schools. For some reason the system-wide approach top down approach must still be employed.

As schools evolve at their own pace and create unique ecologies it’s vital governments and education administrators factor variability and not sameness into all aspects of their operational thinking, be it in relation to the curriculum, teaching, staff selection, home-school collaboration, school planning, marketing, school accountability, resourcing or the use of technology.

The development obliges all external school support bodies and agencies understand where each school sits on the schools’ evolutionary stages continuum, that school’s likely path ahead and to tailor its ‘support’ accordingly if it is to add value to the teaching in that school. If that agency can’t add that value it is better dispensed with, its stultifying presence removed and the schools be left free to take control of their own evolution.

- Helbing, D (2014) ‘What the digital revolution means to us’. Science Business 12 June 2014 – http://bulletin.sciencebusiness.net/news/76591/What-the-digital-revolution-means-for-us

- Lee, M (2014) ‘Teaching in a Digital School: The Differences and the Attributes Needed’. Educational Technology Solutions No.59 2014. Also available at – http://www.malleehome.com

Lee